The following excerpts are from Modern American Schoolhouses – Some Recent Examples of Specialized Buildings Guilbert & Betelle, Architects by Rawson W. Haddon in The Architectural Record, September 1914. This lengthy article is a survey of the firm’s work of that period, before the death of Guilbert. The author ruminates on the not-strictly Gothic eclecticism of these buildings, as I explored in my recent drive through Newark.

Many things have combined to make the school house one of the most complicated of modern architectural problems. Not only are the usual appointments changed extensively from year to year, but the growing tendency to devote the school to the broader educational uses and to various sorts of social betterment and neighborhood work has also brought special problems: and each new use, whether educational or sociological, puts before the architect intricate questions of design to solve.

The multiplication of specialized uses and of the consequent “specialized problems,” has led to the development of specialized architectural firms, made up of men who have studied the school house problem from all its angles and who concern themselves more or less exclusively with school house design. Among these specialists there are,perhaps, few whose work, extending over a period of years, has maintained the high degree of excellence, both in planning and in exterior design–this latter especially–that is noticeable in the work of Messrs. Guilbert & Betelle, of Newark, New Jersey.

The importance of efficiency in plan, of providing a building that can be used for many purposes, both educational and social, and many of them at the same time if necessary, without these different uses interfering with one another: of good circulation, centralized administration and safety from fire and panic, combined with economy of maintenance and first cost, are features, besides the equally perplexing ones of the arrangement of the class rooms themselves, not to be overlooked and problems not to be underrated. Neither, in a modern school, are the idealties to be lost sign of, and for these manifold reasons, besides the fact that they are new, and that each was an attempt at ideal planning, the schools of the firm under consideration are well worth studying.

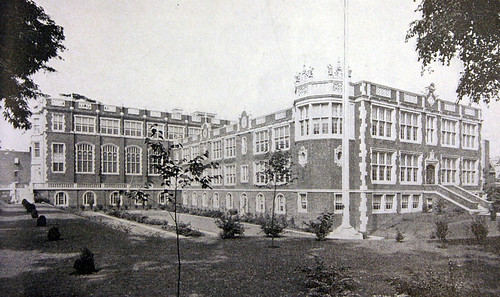

As an example, the Newark Normal School should be given first place because of its successfully designed exterior, as well as for its exceptional arrangement and size. The accompanying plans show the layout of the various rooms. Unusual features are the comparative isolation of the auditorium, an elaborately planned kindergarten “for observation” (this being, as you remember, a normal school), a number of class rooms that are also intended for observation, and a nicely decorated, though rather unfortunately furnished, rest room. In justice to the architects it should be immediately added that they had nothing to do with the selection of this furniture. In the kindergarten an ingle nook with a fire place is provided. Conflicting sources of light, in spite of the prominence given to the bay window in elevation, have been obviated by the use, in the bay, of small oval windows.

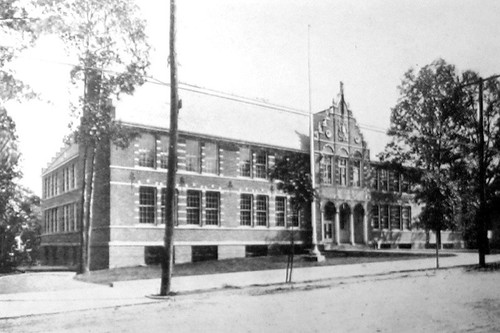

The Ridge School is even more interesting from the point of view of exterior design. Here the problem was an entirely different one, and the solution bears witness to the changed requirements and to a distinct change in surroundings. Being in a high class residential district, it was thought desirable to make the building attractive to an unusual degree, but without additional expense in erection. On the first floor are five class rooms, an auditorium, kindergarten, the administration offices and a library. The arrangement of the auditorium, in its relation to the administration and to the stairs and exits is noteworthy. Used after school hours, the entrance being directly opposite the main entrance of the building, could be effectively closed off by a temporary railing or screen from the corridors and stairs.

Of the work in Newark the School Board Journal says:

“The building activities of the Newark board of education during the past four years have been extraordinary when the size of the city is taken in consideration. Nineteen new buildings and additions have been undertaken, providing for nearly fifteen thousand pupils, in approximately four hundred class rooms. The total cost of these buildings is slightly less than $2,700,000, in itself a great sum of money, but not so large when the amount of accommodations provided with it is taken into consideration. For Newark is erecting high and elementary schools at a general average cost of $180 per child.”

I may add that the Guilbert & Betelle elevations are of especial interest as illustrating an important feature of American architecture. The plants of this firm show a degree of skill and knowledge of school house problems that is not often met with and their schools have established precedents that will naturally be followed by other designers.

But the elevations of their buildings have an interest and a wider significance than any plan could have, and even when the great importance of planning is taken into consideration the fact still remains that these elevations are of interest to every architect in or out of “school house lines.” One might call them, and they would be called as a rule, “Collegiate Gothics.” And Collegiate Gothic is used in school house work, among other reasons, because it adapts itself in a consistent way to the large window openings and small piers that are necessary to successful school house design. And yet these buildings are not, one is glad to say, strictly, or archaeologically, English Collegiate. Neither is the Gothic strictly French, English or Italian Gothic.

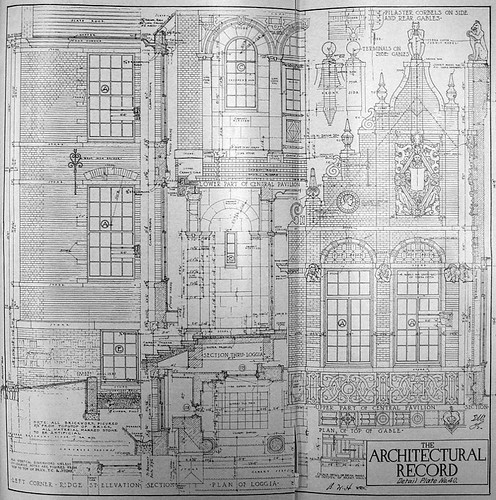

Looking, for instance, at the exterior of the Central Commercial and Manual Training High School, you will notice that after all it is really not Collegiate Gothic at all. There are circular headed window openings on the top floor with Renaissance pilasters between. The terrace entrance is distinctly Renaissance and the heads of the basement windows are arched in a distinctly modern un-Gothic way.

Looking, for instance, at the exterior of the Central Commercial and Manual Training High School, you will notice that after all it is really not Collegiate Gothic at all. There are circular headed window openings on the top floor with Renaissance pilasters between. The terrace entrance is distinctly Renaissance and the heads of the basement windows are arched in a distinctly modern un-Gothic way.

What does this mean? And is any especial meaning attached to the fact that you go through a carefully studied and altogether successful doorway that is “distinctly Renaissance” in the Newark Normal School, into an auditorium that is as successfully designed a “Collegiate Gothic” auditorium as there is in America, without any apparent feeling of the unfitness of going thus suddenly from Renaissance to Gothic and then from Gothic (if you leave by the auditorium entrance) to Renaissance again?

Just what it does suggest will naturally vary according to the person to whom the suggestion comes. To me it suggests a sort of echo of the motto over the Normal School door, “Who Dares to Teach Must Never Cease to Learn,” and I like to think that Messrs. Guilbert & Betelle, in their school work–perhaps without being conscious of it–are teaching us or at least showing us how we may learn to look away for a time from a too close dependence upon historic styles and to walk alone for a season into a more nearly American style of Architecture.

As one looks at these schools, and at the work of many other contemporary designers, one feels more and more that American buildings are becoming so distinctly Americanized that, even though the designs are based upon historic styles, they would certainly appear out of place in surroundings that are not American. And one would not be apt to mistake these schools for anything but what they are–American public buildings.

As one looks at these schools, and at the work of many other contemporary designers, one feels more and more that American buildings are becoming so distinctly Americanized that, even though the designs are based upon historic styles, they would certainly appear out of place in surroundings that are not American. And one would not be apt to mistake these schools for anything but what they are–American public buildings.

American architects, having no traditions that might be called national, must look to other countries for their primary inspiration, but, like every good artist, no matter in what material or medium he may work, the American designer will reach his own national expression by frankly accepting each new problem and buy finding in it an inspiration for new solutions and new endeavors.

wow, cool stuff ! Thank you !